Particles

collected from Earth's upper atmosphere, originally deposited by comets, are

older than our Solar System, scientists say – and these fine bits of

interstellar dust could teach us about how planets and stars form from the very

beginning. These cosmic particles have lived through at least 4.6 billion years

(4,600,000,000).

And these

cosmic particles also traveled across incredible distances, according to the

new research into their chemical composition.

The international team of scientists behind this study is confident that

we're looking at the very basic materials making up the planetary bodies

currently whizzing around our Sun. For anyone studying the origins of the

Universe, it's a fantastic finding.

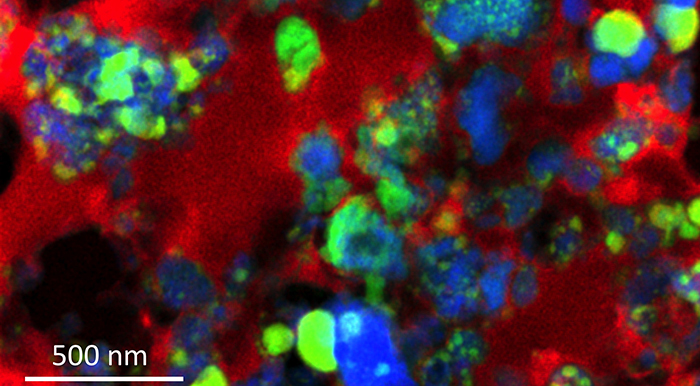

An x-ray

spectrometry map of the grains. (Hope Ishii/University of Hawaii; Berkeley Lab)

"The

presence of specific types of organic carbon in both the inner and outer

regions of the particles suggests the formation process occurred entirely at

low temperatures," says one of the researchers, Jim Ciston from the

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. "Therefore, these interplanetary

dust particles survived from the time before formation of the planetary bodies

in the Solar System, and provide insight into the chemistry of those ancient

building blocks."

This is a

rare chance to study the material that formed our Solar System close up.

Scientists think it developed from a collapsed disk of gaseous clouds around

the Sun, but experts often have to make use of computer simulations to work out

a hypothesis.

Now, they

have their hands on dust that may have actually been there when the planets in

our Solar System were born. The amorphous silicate, carbon, and ice that was

around all those billions of years ago has largely been obliterated or reworked

into the planets we have today, with the original form of these substances now

mainly found in comets.

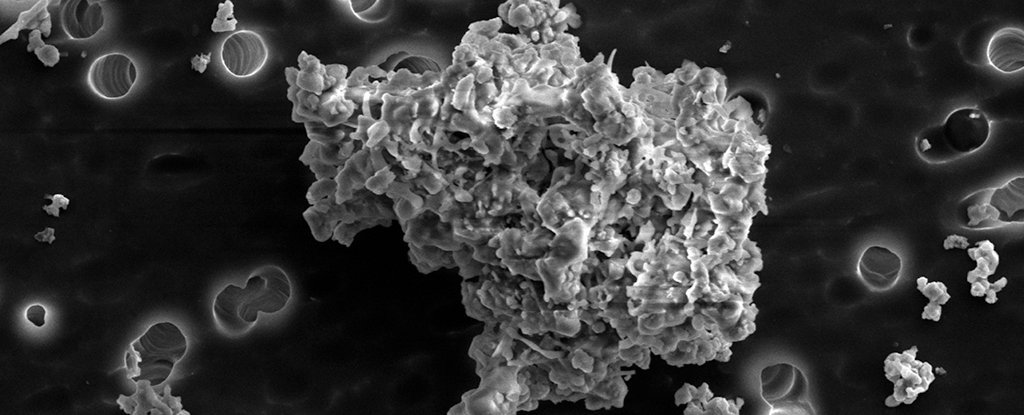

Rather than

catching a comet, the scientists used samples collected by a NASA stratospheric

aircraft, particles burned off comets that had eventually settled high up in

Earth's atmosphere. Using infrared light and electron microscopes, the team analyzed

the chemical composition of the particles. In particular, they looked at a

subgroup of glassy particles called GEMS (glass with embedded metal and

sulfides), measuring just a few hundred nanometers across at most - less than a

hundredth of the thickness of a human hair.

The results

showed these grains were originally fused together in an environment that was

cold and rich with radiation. Even a small amount of heat was enough to break

the bonds in the grains, suggesting they formed somewhere like the outer solar

nebula – the cloud of dust, hydrogen, helium, and other ionized gases out of

which the Solar System formed.

"The

presence of specific types of organic carbon in both the inner and outer

regions of the particles suggests the formation process occurred entirely at

low temperatures," says one of the researchers, Jim Ciston from the

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. "Therefore, these interplanetary

dust particles survived from the time before formation of the planetary bodies

in the Solar System, and provide insight into the chemistry of those ancient

building blocks."

Some kind of

sticky organic material might have been responsible for these grains clumping

together, and eventually forming planets in the cold and empty early years of

the Solar System, the researchers suggest. And while it's too early to draw any

conclusions about what was going on almost 5 billion years ago, the scientists

have plans to study comet dust particles in a lot more depth, to try and unlock

the secrets of the early Solar System.

"This

is an example of research that seeks to satisfy the human urge to understand

our world's origins," says Ishii.

The research

has been published in PNAS.

Article was

originally published on ScienceAlert. Read the Original article here.