If you've

read anything about quantum computers, you may have encountered the statement,

"It's like computing with zero and one at the same time." That's sort

of true, but what makes quantum computers exciting is something spookier:

Entanglement.

A new

quantum device entangles 20 quantum bits together at the same time, making it

perhaps one of the most entangled, controllable devices yet.

This is an

important milestone in the quantum computing world, but it also shows just how

much more work there is left to do before we can realize the general-purpose

quantum computers of the future, which will be able to solve big problems

relating to AI and cybersecurity that classical computers can't.

"We're

now getting access to single-particle-control devices" with tens of

qubits, study author Ben Lanyon from the Institute for Quantum Optics and

Quantum Information in Austria told Gizmodo. Soon "we can get to the level

where we can create super-exotic quantum states and see how they behave in the

lab. I think that's very exciting."

Forget about

"quantum computing" for a second, and just consider the smallest

particles. Particles take on exact values of certain innate properties, the way

coins are either heads or tails. But unlike real coins, you can prepare

particles so they encode both the values of "heads" and

"tails", each with some complex number (like a+bi) associated with

it.

This is only

meaningful after you prepare the particle in that state, and before you measure

it again. Every time you measure it, you'll always get just one of the choices.

But if you prepare and measure the same state a lot of times, you can glean

some information about it.

If you have

two particles, then you can have them interact in such a way that they are

entangled. Even if you separate these particles by great distances, they remain

entangled, an effect that Albert Einstein called "spooky action at a

distance". Now, the complex numbers describe combinations of both

particles' properties, so one particle cannot be explained without the other.

You can tell whether these particles were entangled based on mathematical

correlations that would come up during repeated resulting measurements of them.

If you think

of each of those two-state systems as a weird computer bit, and allow these

bits to entangle, then you can generate strange new quantum-only correlated

statistics when you measure them. Combined with another topic called quantum

interference, this allows for new kinds of devices that can perform computing

algorithms that regular computers wouldn't be able to do.

But

entangling a lot of particles together and keeping them entangled while still

being able to control the individual qubits has been exceedingly difficult.

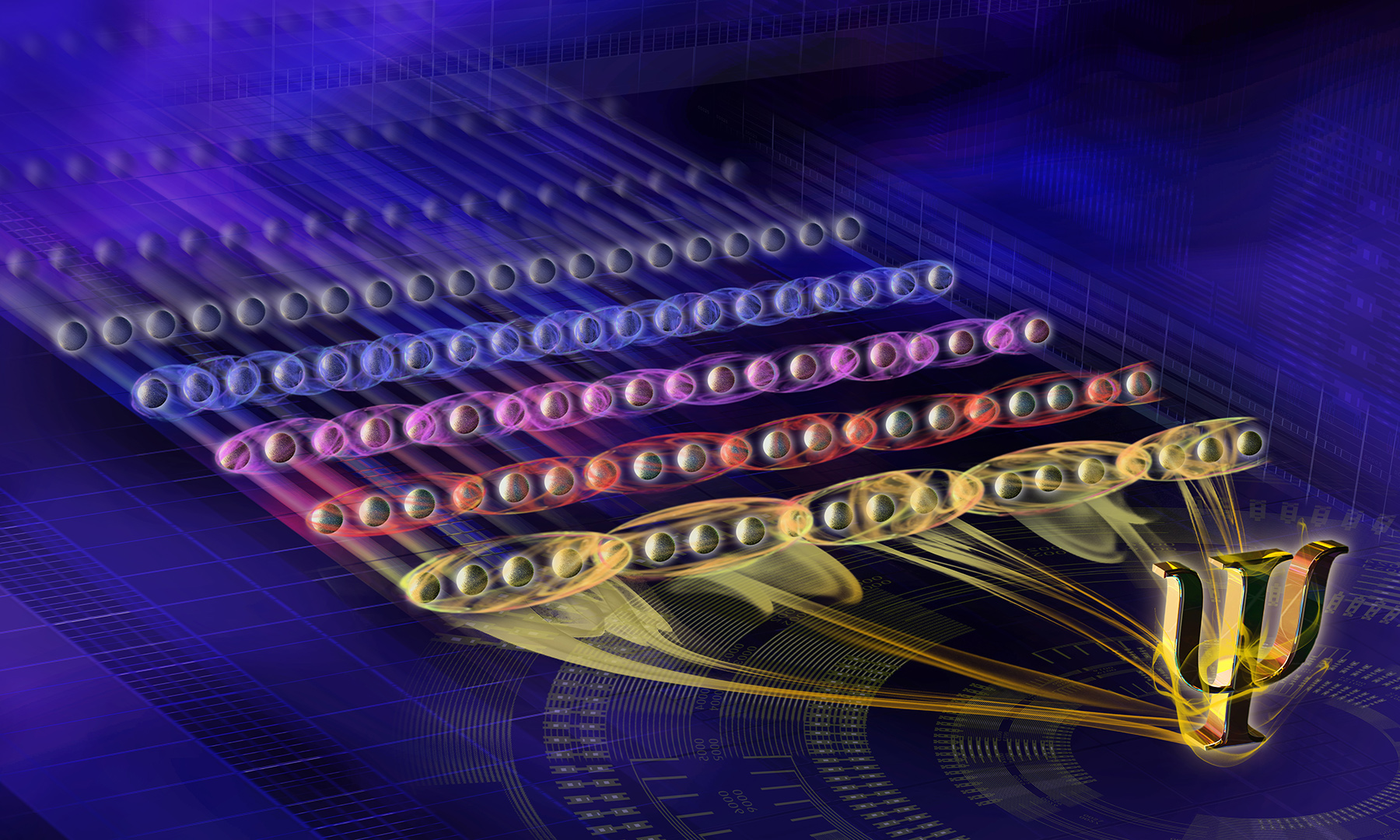

Lanyon and others are now demonstrating a device with qubits as 20 calcium ions

arranged in a line. In these atoms, the outermost electrons can be in one of

two places, with the two places effectively representing the one and zero of a

traditional computer bit. The scientists measure which state the atom is in by

whether it fluoresces (glows under an added energy source) or not. They

entangle these atoms' states using a series of lasers.

The

experimenters watched as all 20 atoms entangled with two other, three other, or

even four other neighbours. They were able to individually manipulate and

measure each qubit, according to the paper published in Physical Review X.

This shows

just how much work there is left to do in the world of quantum computers. Other

researchers have announced computers using a similar technology with 51 or 53

qubits. Google has one that it hasn't quite tested yet with 72 qubits, and

D-wave flaunts their 2000+ qubit machine, but it's a very specific kind of

quantum computer that might not be any faster than a regular computer

performing the same problems.

I asked IBM

about its own quantum computers: "We haven't performed the same experiment

on our IBM Q devices and we are not yet releasing data from our 20-qubit

device," Sarah Sheldon, an IBM quantum computing researcher, told Gizmodo.

A similar experiment was done on the 16-qubit cloud device by an external group

that was able to entangle all 16 qubits, she said.

If you want

the truly universal quantum computers that futurists dream of, you have to be

able to entangle the qubits.

"A key

demonstration of growth in the performance of quantum computers is not simply

the ability to fabricate more devices, but rather putting many qubits to work

simultaneously," Michael Biercuk, professor of quantum physics at the University

of Sydney, told Gizmodo. Additionally, many of the leaders of the pack, like

Google and IBM, make their quantum computers using highly engineered

superconducting circuits, instead of single atoms. This demonstration is a win

for systems that rely on atoms in different states as their qubits.

This

experiment also demonstrates some of the most exotic quantum systems ever made,

said Lanyon. He's particularly interested in nearer-term physics

experimentation: Testing the limits of quantum computing in the lab, instead of

with theory.

Others

thought this advance was important. "It is one step further towards small

scale, general-purpose quantum computers" made from trapped atom systems

like these, University of California Merced physicist Lin Tian told Gizmodo.

We're

inching closer to useful quantum computers, and have gotten excited about a

number of announcements around big quantum devices. But this 20-qubit machine

highlights, once again, that there are a lot of things beyond qubit count that

must be taken into consideration.